Angela Merkel A Pair of Safe Hands

Perceptions of Germany’s chancellor, who is

likely to win re-election on September 22nd, are completely different at

home and abroad

SUPERSIZED and without commentary, a pair of hands went up the other

day on the side of a building just outside Berlin’s main train station,

with Germany’s parliament and government buildings in clear view. The

idiosyncratic bracing of thumb and fingers made the digits on the poster

instantly recognisable as belonging to Angela Merkel, who is up for

re-election as chancellor on September 22nd. The “Merkel rhombus” has

become something of a symbol.

This billboard in Berlin features only 3 letters along with those iconic hands, clearly supporting Merkel's CDU Party.

Asked about it, she replies, in a disarming and characteristic

deadpan, that she adopted the position to solve a practical problem, as

any trained scientist would (she earned her PhD with a dissertation on

quantum chemistry). The problem was what to do with those hands. The

solution was to neutralise them against each other, which happens to be

pleasingly symmetrical and also pushes the shoulders up, improving

posture.

The explanation is pure Merkel—unpretentious, pragmatic, artfully

plain. With a similarly choreographed candour she has let it be known

that she likes to cook potato soup for her husband (a scientist who

otherwise stays out of public view). She does her own shopping,

occasionally getting lost in the supermarket aisles. Mrs Merkel “fits

the cliché that we Germans have of ourselves: frugal, sombre, awkward

and a bit unpolished in a likeable way,” says Ralph Bollmann, author of

one of a ream of biographies published this year. That common touch, he

thinks, is why the Germans identify so much with their chancellor that

in the past few years they have started to call her

Mutti—“Mum”.

The rhombus makes for a striking poster. As telling, though, is what

the huge poster lacks. There is only one tiny bit of text: the initials

CDU, tucked in the corner. They stand for the Christian Democratic

Union, the centre-right party that Mrs Merkel leads, a big tent of

churchgoers, conservatives and free-market liberals. Parties and

platforms, not personalities, are supposed to play the lead role in

German parliamentary elections. But this time, for the CDU, Mrs Merkel’s

person is the platform.

What is that platform’s content? Outside Germany, Mrs Merkel is

identified above all with a particular stance in the euro crisis, one

which says it can only be solved with “austerity” (meaning brutal budget

cuts) on the part of formerly profligate governments and wider economic

reforms to make the entire euro zone competitive again. This explains

the cheeky banners Irish football fans held up during last year’s

European championship: “Angela Merkel thinks we’re at work”. It also

accounts for the odious posters of Mrs Merkel defaced with a Hitler

moustache brandished by demonstrators in Greece.

Ganz, Schön, Lustig

Germans see things differently. Mrs Merkel has achieved close to

nothing of what she promised in previous election manifestos. There has

been no overall tax simplification, for example, only a few giveaways to

special interests. She has undertaken no big reform—the last one,

liberalising Germany’s labour market, occurred a decade ago under her

predecessor, Gerhard Schröder. Where she has made bold domestic changes,

above all in deciding to give up nuclear power after the 2011 disaster

at Fukushima in Japan, she has been adopting policies already favoured

by the opposition parties. To Germans, therefore, Mrs Merkel is the

opposite of ideological. She is a caregiver, like a

Mutti, not a taskmaster, like her Irish or Greek caricatures.

By temperament, Mrs Merkel tries to slow political processes down.

She also tries to break down problems into discrete units, observing and

testing each solution separately before moving on to the next, as a

good scientist would. That is what she has done in successive Brussels

summits dealing with the euro crisis. Where the world saw a dogmatic

Prussian forcing others to be disciplined, the Germans saw a chancellor

giving ground to demands from crisis countries and France (on bail-outs,

rescue funds and banking union), but cautiously and in the smallest

possible increments. As taxpayers, Germans felt she was protecting them

even as they understood that more concessions might follow. Mr Bollmann

sees this ability to accustom the Germans gradually to new realities,

and to know when they are ready to accept more, as Mrs Merkel’s

particular genius.

Her “politics of small steps” is communicated in a way her countrymen

appreciate and foreigners find baffling. Mrs Merkel speaks with

soothing tones and simple, reassuring phrases which often have little

content—a “sanitised Lego language, snapping together prefabricated

phrases made of hollow plastic,” as Timothy Garton Ash at Oxford

University describes it. In part, Mr Garton Ash allows, this is just the

modern German fashion. “Because of Hitler, the palette of contemporary

German political rhetoric is deliberately narrow, cautious, and boring.”

But Mrs Merkel has taken it to new extremes of moderation.

Peer Steinbrück, who as leader of the Social Democrats (SPD) is her

main rival in the elections, parodies her well. When he says, “A good

foundation is the best precondition for a solid basis in Europe, ladies

and gentlemen,” it usually brings the house down because it really does

sound like Mrs Merkel. In so doing it allows Mr Steinbrück to position

himself, in contrast, as one who dishes out “straight talk”—

Klartext.

To Mr Steinbrück’s frustration, however, his straight talk often leads

to gaffes. When he says that he would not pay less than €5 ($6.63) for a

bottle of Pinot Grigio the German public spends a few days affecting

outrage that a Social Democrat with blue-collar interests at heart would

say such a thing. But when Mrs Merkel does her

Mutti-talk, she gets away with it.

Once and future chancellors

A more personal lunge at Mrs Merkel over the euro crisis missed the

mark. Trying to make her incrementalism into a shortcoming, Mr

Steinbrück suggested that Mrs Merkel lacked “feeling” for the European

project because she spent the first 36 years of her life in East

Germany, outside the European Communities from which the EU grew. It is

true that she has a different (though not necessarily lesser) emotional

connection to the EU than that felt, say, by Helmut Kohl, the pro-French

CDU chancellor who oversaw German reunification and the conception of

the euro and who brought Mrs Merkel into national politics. But as Mr

Steinbrück discovered, a lot of people were offended that he could

suspect Mrs Merkel of insufficient euro-passion merely because she grew

up an

Ossi (easterner).

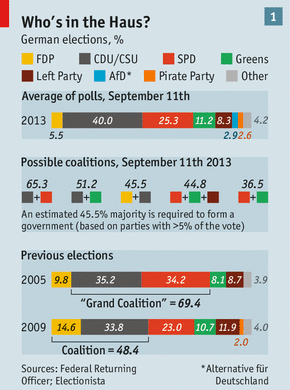

ECONOMIST Graphic listing Germany's main political parties and their shifts since 2005.

A good bit of what passes for campaign fisticuffs between these two

politicians is in fact kabuki. They know and respect each other. In Mrs

Merkel’s first term, from 2005 to 2009, she led a “grand coalition”

between the CDU and the SPD (see chart 1) with Mr Steinbrück as her

finance minister. They worked well together. When the financial crisis

struck in 2008, the two gave a joint press conference to assure German

savers that their bank deposits were safe. That image endures as the

moment when the German public calmed down.

Both are also known for a wry sense of humour. In Mr Steinbrück’s

case, it is broadly ironic (he blames his Danish grandmother for

teaching it to him). Mrs Merkel’s humour tends nowadays to be low-key

and reserved for private occasions, or at least situations removed from

the public glare. The block of flats in which she lives has fewer

tenants than it did, for security reasons; so her doorbell, marked

discreetly with her husband’s name, Sauer, sits in a row with others

marked Ganz, Schön, Lustig, Schön, Ganz (roughly translated: really

quite funny, quite really). She is also a woman of culture and emotion.

The risk of controversy does not stop her attending the Wagner festival

in Bayreuth every summer; while she will sit through and enjoy the Ring

Cycle, her particular favourite is said to be “Tristan and Isolde”, with

its morbid and tragic beauty.

A good foundation

One of the problems for the SPD and the other large opposition party,

the Greens, in running against Mrs Merkel is that, in an admirable

display of responsibility, they both voted with her at every step in the

euro-rescue. Yes, the Greens, in particular, would have liked to go

faster and would have been open to Eurobonds (issued separately by each

euro-zone government but guaranteed by all), which Mrs Merkel has ruled

out. Bolder action at the beginning might have nipped the crisis in the

bud, says Jürgen Trittin, a leading Green; instead Mrs Merkel “always

delays, then eventually does what we said”. But to most Germans, this

just sounds like nitpicking.

Predict the German election result with our interactive coalition tracker

More annoyingly for Mr Trittin, voters now have the same blurred view

of the parties’ differences in energy policy. For most of the 30 years

since the Greens entered parliament, their signature demand was for

Germany to say

Nein, Danke to nuclear power.

Having previously backed nuclear power, in the days after Fukushima, Mrs

Merkel made the most abrupt volte-face of her career. She decided to

start turning the plants off and to exit nuclear power altogether by

2022.

For the Greens, this should have been a huge victory. Instead, it allowed Mrs Merkel to neutralise the entire subject. The

En ergiewende

(“energy turn”), which also encompasses a large and generously

subsidised push into renewable energy, means putting up prices when in

competitors such as America energy is getting cheaper; this looks

worrying to some businesspeople. But there is a consensus behind it

among all the main parties. Mr Trittin is reduced to bickering about

operational details (power lines and so forth) rather than attacking Mrs

Merkel head-on.

This is part of a pattern that has been called Merkelvellianism. By

small, sly moves, Mrs Merkel has inched the CDU leftward, poaching one

policy after another from her centre-left rivals. For decades the CDU

favoured military conscription. Then Mrs Merkel abolished the draft, as

the left wanted. When the SPD and Greens promised a minimum wage, Mrs

Merkel quickly put forth a similar idea (albeit with flexible wage

floors across regions and industries). When old-age poverty became the

issue earlier this year, she promised to provide higher pensions for

older mothers. When the left called for rent controls this summer, she

supported them, too. On only one weighty subject does she squarely

oppose the left. They want to raise taxes; she does not.

Mr Steinbrück reaches for every available metaphor to paint Mrs

Merkel as a plagiarist lacking any conviction. Living in a country run

by her is like driving endlessly round a roundabout—few fender benders

but also no direction; her finger doesn’t point the way but only

measures which way the wind is blowing: and so forth. Mrs Merkel drives

some people in her own centre-right camp just as batty. A book by a

veteran CDU adviser calls her Germany’s “godmother”—in the mafia, not

the maternal, sense—a person with no values who betrays the ones held by

the CDU whenever it suits her. Peter Kohl, the estranged son of the

former chancellor, has said that he will abstain from voting because

Germany now has, in effect, three social-democratic parties: the SPD,

the Greens and Mrs Merkel’s CDU. Outside Germany, she is seen as

unbending. (“

Austerit ät,

that new word: it sounds so evil,” Mrs Merkel jokes in her aw-shucks

way.) Inside Germany, she looks as stiff as a plateful of spaghetti.

The best precondition

There is strategic method in her flexibility. By creeping into the

political terrain of the opposition parties, Mrs Merkel hopes to reduce

their supporters’ readiness to go to the polls. In doing so she knows

that she will induce some CDU supporters to stay at home, too. But as

long as she dampens turnout more for the parties of the left than for

her own, she wins. Her political consultants call it “asymmetric

demobilisation”.

It is not an elegant or very principled strategy, but it seems a

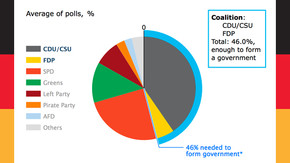

workable one. The CDU is the strongest party, with about 40% in most

polls. Though it will not secure an absolute majority, most coalition

scenarios play out well for Mrs Merkel. One possibility is a continued

partnership between the CDU, its Bavarian sister party (the CSU) and the

liberal Free Democrats (FDP), her current coalition partner. Another

possibility, which would provide a bigger majority but trickier internal

politics, is a grand coalition between the CDU and the SPD like the one

that Mrs Merkel ran in her first term. Mr Steinbrück has said that he

would not serve in such a government again, but that is not in itself a

deal breaker.

A third option is a pact with the Greens. This is less likely because

the Greens are at the moment further to the left than the SPD on such

issues as tax hikes. But there are moderate greens, especially in

south-western Germany. And the party, which shares power in six states,

and has shared it with the CDU at state level in the past, is hungry for

a return to federal government.

By contrast, an SPD-Green coalition, the only one that Mr Steinbrück

has said he would accept, has almost no chance of winning a majority.

The only remaining risk to Mrs Merkel is thus an alliance between all

the parties of the left, including the party called the Left. But the

Left is a pariah in mainstream politics because of its roots in East

Germany’s communist party and its goal of leaving or dissolving NATO. Mr

Steinbrück wants no part in such a “red-red-green” pact, though others

in his party could enter one without him.

Mrs Merkel thus has a good chance of staying in power. A victory

would not be an endorsement of her domestic record, since that record is

muddled. Instead, it would show that Germans forgive her for not having

clear visions at home because she has governed during such unusual

times. The global financial crisis began in her first term and spilled

over into the euro crisis in her second. Disaster management took

precedence over domestic reform.

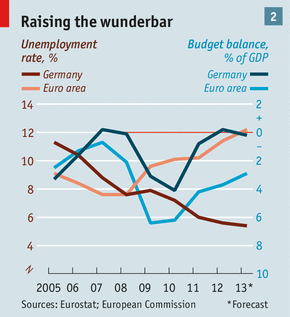

And Germany has without question managed the crisis well (see chart

2). Tax revenues are gushing; the federal government could start

repaying its debt in 2015. Youth unemployment is the lowest in Europe.

Part of this is down to luck. Germany happens to be good at making the

industrial goods that strong economies like China have been demanding.

Part of it is down to Mr Schröder’s reforms, which made Germany’s labour

market more flexible. But what Germans see is that, while many of its

EU partners are struggling, Germany under Mrs Merkel looks strong.

If Mrs Merkel has a vision, it is that the euro zone and the entire

EU should become strong, too. “I experienced the collapse of the German

Democratic Republic, I don’t want to see the EU falling behind,” she has

said. Her advisers believe that the trauma of 1989 informs her view of

the euro zone today. Mrs Merkel often adds a statistic: that Europe has

7% of the world’s population, 25% of its output and 50% of its welfare

spending. This is her way of warning that the status quo may not be

affordable for much longer.

A solid basis in Europe

Europe “has no legal right to be leading in world history,” she says.

“So we have to be careful that solidarity also leads to results, lest

we all get weak together.” This message is aimed in part at France,

Germany’s longtime partner, which is not reforming as fast as Mrs Merkel

would like. In part, she is addressing Spain, Portugal and Greece, to

encourage them to keep reforming. And in part she is talking, softly but

sternly, to the Germans, lest they forget that as recently as the

1990s, Germany was called “the sick man of Europe”.

Keeping the European family healthy takes never-ending hard work and forbearance, says the Protestant pastor’s daughter and

Mutti of her nation. For an otherwise protean woman, such sentiments probably do come from conviction.